There is no guarantee that a great artist will be an admirable person. Many sublimely gifted musicians, painters, sculptors, writers and actors fail as human beings. Dave Brubeck was on the positive end of the scale. Among the dozens, perhaps hundreds, of obituaries and remembrances of Brubeck that have emerged since his death yesterday morning, a thread becomes clear: those who knew him emphasize that his extraordinary musicianship went hand in hand with kindness, generosity, humor and concern for the human condition.

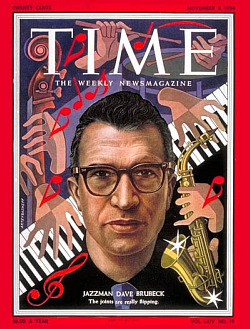

I became aware of all of those facets of Brubeck’s makeup on our first encounter. His quartet played a concert at the University of Washington in Seattle in the winter of 1955. As recounted elsewhere, that is when I also met Paul Desmond. Their stars were on the rise. The year before, Brubeck was the subject of a TIME magazine cover story. In those days in the US that was the apogee of popular recognition. He was quickly becoming famous. After the concert, there was a party for the quartet at the home of an admirer.

For much of the evening Brubeck, the late pianist Patti Bown (pictured) and I sat and talked about the section of the TIME profile that dealt with Dave’s attitude toward racial matters. Patti was a vital member of Seattle’s mixed and mostly tolerant jazz community. As we mulled over the absurdity and reality of race-based prejudice, the conversation varied between intensity, laughter and stretches of contemplative silence. This was years before the civil rights movement gained momentum. Dave recited a verse he wrote that became one of the most widely quoted parts of the TIME article.

Seven years later, Louis Armstrong sang that verse in Dave and Iola Brubeck’s musical The Real Ambassadors, an extended paean to tolerance, cultural diplomacy and the power of music to unify people and nations. Brubeck, Armstrong, Carmen McRae and the vocal group Lambert, Hendricks and Ross recorded it in an album but performed it publicly only at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival. It is long past time for a full-scale revival.

After Eugene Wright became the group’s bassist in 1956, the DBQ played black-owned clubs and hotel lounges in the South, bookings of a racially mixed group, all but unheard of below the Mason-Dixon line. Brubeck’s stand against discrimination became even stronger as the decade wore on. Here’s a passage from my biography accompanying the Brubeck CD collection Time Signatures.

Four of Dave’s sons—Darius, Chris, Danny and Matthew—became professional jazz artists. He took time and made donations to also help scores of aspiring musicians, not least through his support of The Brubeck Institute based at his alma mater, the University of the Pacific in California. Stories of Brubeck’s generosity abound, not because he told them but because the recipients of his thoughtfulness did. I am one of them. During the two-and-a-half years that I researched and wrote my Paul Desmond biography, Dave and Iola allowed me to spend hours with them at their house on its 20 acres in Connecticut, which Desmond long ago named the Wilton Hilton. Without their input and guidance, the book would have been impossible. When it was time for the book to come out, The Brubecks agreed to co-host the book party at Elaine’s restaurant, Paul’s cherished New York refuge. Without their involvement, publisher Malcolm Harris and I would not have had the turnout of prominent people who attended. What a night that was.

After the TIME magazine cover story and the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s elevation from obscurity and near-poverty, the sniping began. They had committed the sins, unpardonable in some quarters, of popular success and solvency. It’s an old story, familiar to Cannonball Adderley, for instance, and to The Modern Jazz Quartet and, more recently, to Diana Krall; if you are in demand and making money, you sold out. Many musicians once sought or invented reasons to dismiss Brubeck’s music: it didn’t swing, it wasn’t hip; he wrote some nice tunes but he wasn’t much of a pianist; he doesn’t deserve a great player like Desmond. On the other hand, “Desmond,” a prominent tenor saxophonist once told me, “sounds like a female alcoholic.” You don’t often hear jibes about Desmond anymore, or the cracks about Brubeck’s piano playing. People seem to have started listening to the music and ignoring the societal effluvia. In Brubeck’s last couple of decades the resentments based in sociology, jealousy, clannishness and envy began to fall away. Young musicians of all stripes study his music, play his tunes, revere him as someone to emulate. Dave lived long enough to see the change. It must have been gratifying to him.

In the long run, it’s his music that matters. It will have a long run.

The Dave Brubeck website has a message from his surviving children (Michael died in 2009). It also has extensive information about his career, photographs spanning decades, and Dave playing Christmas music, beginning with a bluesy “Jingle Bells.”

Since Rifftides hit the web in early 2005, it has posted more than 200 items about Brubeck or touching on him and his music. If you care to browse them, carve out some time and click here.

I became aware of all of those facets of Brubeck’s makeup on our first encounter. His quartet played a concert at the University of Washington in Seattle in the winter of 1955. As recounted elsewhere, that is when I also met Paul Desmond. Their stars were on the rise. The year before, Brubeck was the subject of a TIME magazine cover story. In those days in the US that was the apogee of popular recognition. He was quickly becoming famous. After the concert, there was a party for the quartet at the home of an admirer.

For much of the evening Brubeck, the late pianist Patti Bown (pictured) and I sat and talked about the section of the TIME profile that dealt with Dave’s attitude toward racial matters. Patti was a vital member of Seattle’s mixed and mostly tolerant jazz community. As we mulled over the absurdity and reality of race-based prejudice, the conversation varied between intensity, laughter and stretches of contemplative silence. This was years before the civil rights movement gained momentum. Dave recited a verse he wrote that became one of the most widely quoted parts of the TIME article.

They say I look like God, Could God be black my God! If both are made in the image of thee, Could thou perchance a zebra be?

Seven years later, Louis Armstrong sang that verse in Dave and Iola Brubeck’s musical The Real Ambassadors, an extended paean to tolerance, cultural diplomacy and the power of music to unify people and nations. Brubeck, Armstrong, Carmen McRae and the vocal group Lambert, Hendricks and Ross recorded it in an album but performed it publicly only at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival. It is long past time for a full-scale revival.

After Eugene Wright became the group’s bassist in 1956, the DBQ played black-owned clubs and hotel lounges in the South, bookings of a racially mixed group, all but unheard of below the Mason-Dixon line. Brubeck’s stand against discrimination became even stronger as the decade wore on. Here’s a passage from my biography accompanying the Brubeck CD collection Time Signatures.

Wright was not the first black musician in the Brubeck quartet. Wyatt “Bull” Reuther was the bassist in 1951. Drummer Frank Butler also worked briefly with Brubeck in the early days. But Gene’s advent coincided with the upswing in popularity that increased the demand for the band and put it in high visibility. As a result, there were problems that disturbed Brubeck’s sense of fairness and his passionate belief in racial justice and equality.

He cancelled an extensive and lucrative tour of the South when promoters insisted that he replace Wright with a white bassist. He refused an appearance on the Bell Telephone Hour, a Sunday evening television program of immense prestige and huge audience, when the producers insisted on shooting the quartet so that Wright could be heard but not seen. The networks were convinced that the public was incapable of accepting the sight of black and white performers together. Brubeck found the hypocrisy unsupportable.

Four of Dave’s sons—Darius, Chris, Danny and Matthew—became professional jazz artists. He took time and made donations to also help scores of aspiring musicians, not least through his support of The Brubeck Institute based at his alma mater, the University of the Pacific in California. Stories of Brubeck’s generosity abound, not because he told them but because the recipients of his thoughtfulness did. I am one of them. During the two-and-a-half years that I researched and wrote my Paul Desmond biography, Dave and Iola allowed me to spend hours with them at their house on its 20 acres in Connecticut, which Desmond long ago named the Wilton Hilton. Without their input and guidance, the book would have been impossible. When it was time for the book to come out, The Brubecks agreed to co-host the book party at Elaine’s restaurant, Paul’s cherished New York refuge. Without their involvement, publisher Malcolm Harris and I would not have had the turnout of prominent people who attended. What a night that was.

After the TIME magazine cover story and the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s elevation from obscurity and near-poverty, the sniping began. They had committed the sins, unpardonable in some quarters, of popular success and solvency. It’s an old story, familiar to Cannonball Adderley, for instance, and to The Modern Jazz Quartet and, more recently, to Diana Krall; if you are in demand and making money, you sold out. Many musicians once sought or invented reasons to dismiss Brubeck’s music: it didn’t swing, it wasn’t hip; he wrote some nice tunes but he wasn’t much of a pianist; he doesn’t deserve a great player like Desmond. On the other hand, “Desmond,” a prominent tenor saxophonist once told me, “sounds like a female alcoholic.” You don’t often hear jibes about Desmond anymore, or the cracks about Brubeck’s piano playing. People seem to have started listening to the music and ignoring the societal effluvia. In Brubeck’s last couple of decades the resentments based in sociology, jealousy, clannishness and envy began to fall away. Young musicians of all stripes study his music, play his tunes, revere him as someone to emulate. Dave lived long enough to see the change. It must have been gratifying to him.

In the long run, it’s his music that matters. It will have a long run.

The Dave Brubeck website has a message from his surviving children (Michael died in 2009). It also has extensive information about his career, photographs spanning decades, and Dave playing Christmas music, beginning with a bluesy “Jingle Bells.”

Since Rifftides hit the web in early 2005, it has posted more than 200 items about Brubeck or touching on him and his music. If you care to browse them, carve out some time and click here.