Each entry in Will Friedwald's new book, A Biographical Guide to the Great Jazz and Pop Singers, goes off like a firecracker. There are no dull openings, there's plenty of mischievous humor and pop-culture references, and most of Will's positions on singers are provocative. And in some cases, you may disagree with his take. That's what makes his “essaypedia" interesting. The reasoning for one singer over another is personal. But each of Will's points is well argued and all are designed to get you thinking.

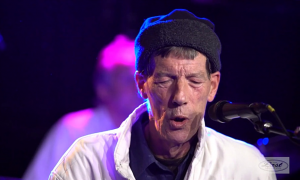

Case in point: Here's his opening to “Little" Jimmy Scott:

“Jimmy Scott, who for most of his career was officially billed as 'Little Jimmy Scott,' is the living embodiment of what novelist Nick Hornby identifies as the central dilemma of pop music. To paraphrase the opening of [Hornby's] High Fidelity: 'Did I start listening to Little Jimmy Scott to help me deal with my heartache, or did I get my heart broken by listening to too many Little Jimmy Scott records?'

“Sometimes when you're feeling down, you have the mistaken idea that things can't possibly get any worse. Well, you're wrong—they can, and probably will. By the time you get all the way down to miserable, then even bad starts to look good to you. Jimmy Scott can capture that feeling like no one else."

In Part 2 of our conversation, Will talks about why music after 1960 is not considered part of the American Songbook and why the music of the last 50 years is often unsuitable for serious jazz and pop singers:

JazzWax: What were the big cultural shifts that made jazz and pop singing less significant today in the marketplace?

Will Friedwald: There was a gradual transition from pop music having a swing beat to having a rock beat—a shift that started in the mid-1950s. But more importantly, there was a philosophical shift. Even in the early years of rock 'n' roll, pop music functioned mostly as it had before.

JW: How so?

WF: You had singers and you had songwriters. Two separate jobs. Elvis Presley didn't operate fundamentally any differently than Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra. He made recordings and he made movies. The shift from singers and songwriters to singer-songwriters was a much more devastating turn of events that pretty much washed away everything that came before it.

JW: This starts roughly when?

WF: After the Beatles and Bob Dylan, the idea of singing a song that you didn't write yourself seemed hopelessly bourgeois, passé and “establishment." Yet from that moment on, with the strong exception of a few upper-bracket types such as Dylan, Lennon and McCartney, pop music was both compromised and downsized.

JW: So we have them to blame for the shift?

WF: Not them specifically. The big chasm in pop history isn't so much the gap between crooners and rockers but, instead, between “pure" singers and composers and the all-in-one singer-player-songwriters who think they can do it all.

JW: Wasn't the result something of an improvement, a shift away from “moon-June" and toward more meaningful, personal storytelling?

WF: Songwriter Jimmy Webb told me about a comment he heard from Joni Mitchell: “We used to have lyricists, we used to have composers, we used to have singers, we used to have accompanists and arrangers. Now we have one person doing all those jobs and in a half-assed way!"

JW: I notice that Astrud Gilberto, Georgia Gibbs and Dionne Warwick didn't make the cut for your book. Why not?

WF: The focus, first of all, was on artists who sang the American Songbook. But even though I cover 150 to 200 singers, from the age of wax cylinders to the age of MP3s, no book is going to be big enough to cover everybody. The focus was on artists who were iconic, influential and incredibly great.

JW: In a nutshell, what was the criterion?

WF: I wanted to feature singers who had a lasting impact on the way that the Songbook has been sung. Obviously there was a great deal of subjectivity. I had to make the case for a number of artists who were outside of my personal taste. Likewise, my editor Bob Gottlieb would request the inclusion of singers I hadn't thought of.

JW: So did Gilberto and Warwick not qualify or were they overlooked?

WF: Neither Gilberto nor Warwick, as far as I know, sang the Songbook exclusively, or frequently enough to warrant inclusion. Besides, I never thought of either one of them as heavy hitters.

JW: How so?

WF: Gilberto was the first to make a practice of bringing the bossa nova to North American songs, for which she deserves credit. But I always thought of her voice as colorless and flat. Someone once said that she sings with all the pizzazz of a UN interpreter. As for Warwick, I honestly have never paid much attention to her. Your recent interview and post on her may cause me to re-think my position.

JW: What about Georgia Gibbs?

WF: There are a few references to Gibbs in the book, but I had to make a judgment call there. Frankly, her career wasn't big enough. She didn't have hits that compete with Jo Stafford's or Patti Page's. And as a stylist, I don't think she really competes with Peggy Lee or Blossom Dearie.

JW: What do you think of Gibbs?

WF: She was a talent and she had a long career. But she never really attained the upper brackets in her band-singer phase or as a solo act in the 1950s, when she was viewed, incorrectly, merely as a cover artist.

JW: What then were the qualifications?

WF: I was looking for artists who were either incredibly popular—with big massive careers—or incredibly influential. The two aren't necessarily related. Frankie Laine sold a zillion records and was massively popular. But nobody tries to sound like him. As for incredibly great but less popular, two examples are Jeri Southern and Joe Mooney. Both had relatively small careers but were disproportionately influential.

JW: Why do we hear today endless American Songbook renditions but so few interpretations of '60s and '70s songs?

WF: With good reason. When singer and songwriter and arranger and accompanist were separate professions, the songs that came out of that era were essentially intended to serve as templates for interpretation (and even improvisation).

JW: What do you mean?

WF: When Harold Rome wrote the score for Call Me Mister in 1946, he knew that whoever sang his songs on Broadway would do it one way. Whatever big bands recorded it would play it a different way, the pop singers who sang it on the radio would do it their own way, and the more distinctly jazz-oriented stylists of the era, from Ella Fitzgerald to the King Cole Trio, would find yet another way to do the same song.

JW: Songs from the 60s and '70s were crafted differently?

WF: They didn't lend themselves to the same kind of interpretation. From the Beatles and Bob Dylan onward, it was generally expected that the composer and performer would be the same person—occasionally for better, generally for worse.

JW: Aren't we splitting hairs? Music is music and a good song is a good song, no?

WF: Yes, but the point I'm making is that the Songbook lends itself better to interpretation. The songwriter and singer Dory Previn made an interesting distinction. She said that when she was writing songs with her then-husband Andre Previn in the early '60s, she describes that traditional style of songwriting as “objective." Ten years later, when she was writing her own songs—music and lyrics—and singing them herself, she calls that kind of songwriting “subjective."

JW: Meaning?

WF: The songs she wrote later in the singer-songwriter era could pretty much be sung only by her. They were so personal and came so directly out of her unique experience. But this goes beyond just lyrics.

JW: In what regard?

WF: Pianist Bill Charlap once pointed out to me that songs written mostly for Broadway and Hollywood in the years before 1960 were explicitly constructed harmonically and melodically to encourage interpretation. They use higher intervals—ninths and beyond—which open up a wide range of harmonic possibilities. The post-1970 singer-songwriter songs don't have that inherent musicality, and, consequently, there's only so much you can do with them.

JW: So songs by James Taylor are out?

WF: Nothing against James Taylor, but it's much harder to improvise on one of his songs than on something by Cy Coleman.

JW: Does this extend to post-1960s Broadway?

WF: Yes. Since 1970, Broadway's music has been much more “subjective." In the aftermath of Stephen Sondheim, songs tend to be more and more completely integrated into the plots of their shows, and harder to extract and make work independently. Sondheim is far from tuneless and amusical, of course. I think he's an even better composer than he is a lyricist. But there's a reason why the Shelly Manne Trio never recorded a jazz treatment of Sondheim's Pacific Overtures.

JW: Are we treating 1960 a bit like some continental divide?

WF: No, no. I'm not saying that there haven't been dozens or even of hundreds of excellent songs written in the last 50 years. But whatever the total, it's nothing, not even a drop in the bucket, compared to the thousands upon thousands of great songs written, as they say, back in the day.

JW: Can too much pop ambition and polish spoil a jazz interpretation of the Songbook?

WF: I have heard people say that, but I don't know if it's necessarily true. Some voices are smooth and polished and others are rough and scabrous. Some singers have more appealing natural voices than others, but obviously it's what you do with it that counts.

JW: For example?

WF: Joe Mooney could barely whisper in tune, yet he phrased so brilliantly that singers like Tony Bennett and Frank Sinatra cited him as an influence. With her tiny, baby-doll voice, Blossom Dearie had one of the most distinctive sounds around.

JW: Is the opposite true as well?

WF: Yes. I don't think there is such a thing as a “jazz voice" sound, unless it sounds exactly like Louis Armstrong's. We associate the rougher voices with the blues—like the crackling chops of Ray Charles. But Joe Williams had a voice smoother than most crooners. If Ella Fitzgerald had improvised less and concentrated more on looking for hit singles, she could have easily competed in the pop stakes with Jo Stafford and Nat King Cole. Sarah Vaughan probably could have sung Puccini or Verdi with a little effort—certainly better than Aretha Franklin.

JazzWax pages: Will Friedwald's A Biographical Guide to the Great Jazz and Pop Singers (Pantheon) can be found here.

Five more picks. I asked Will Friedwald for a list of his 10 favorite little-known albums by jazz and pop singers. Here's the second set on his list. The first five are in Part 1 of this interview. Five more, in alphabetical order:

6. Jackie Paris: The Song is Paris (Impulse) 7. Louis Prima: On Broadway (United Artists) 8. Frank Sinatra: Close to You (Capitol) 9. Jeri Southern: You Better Go Now (Decca) 10. Kay Starr: I Cry By Night (Capitol)

JazzWax clip: Think you know Kay Starr? Here she is singing Baby Won't You Please Come Home from I Cry By Night with Mannie Klein (tp), Gerald Wiggins (p), Al Hendrickson (g), Joe Comfort (b) and Lee Young (d) (Ben Webster appears on other tracks on the album)...

Case in point: Here's his opening to “Little" Jimmy Scott:

“Jimmy Scott, who for most of his career was officially billed as 'Little Jimmy Scott,' is the living embodiment of what novelist Nick Hornby identifies as the central dilemma of pop music. To paraphrase the opening of [Hornby's] High Fidelity: 'Did I start listening to Little Jimmy Scott to help me deal with my heartache, or did I get my heart broken by listening to too many Little Jimmy Scott records?'

“Sometimes when you're feeling down, you have the mistaken idea that things can't possibly get any worse. Well, you're wrong—they can, and probably will. By the time you get all the way down to miserable, then even bad starts to look good to you. Jimmy Scott can capture that feeling like no one else."

In Part 2 of our conversation, Will talks about why music after 1960 is not considered part of the American Songbook and why the music of the last 50 years is often unsuitable for serious jazz and pop singers:

JazzWax: What were the big cultural shifts that made jazz and pop singing less significant today in the marketplace?

Will Friedwald: There was a gradual transition from pop music having a swing beat to having a rock beat—a shift that started in the mid-1950s. But more importantly, there was a philosophical shift. Even in the early years of rock 'n' roll, pop music functioned mostly as it had before.

JW: How so?

WF: You had singers and you had songwriters. Two separate jobs. Elvis Presley didn't operate fundamentally any differently than Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra. He made recordings and he made movies. The shift from singers and songwriters to singer-songwriters was a much more devastating turn of events that pretty much washed away everything that came before it.

JW: This starts roughly when?

WF: After the Beatles and Bob Dylan, the idea of singing a song that you didn't write yourself seemed hopelessly bourgeois, passé and “establishment." Yet from that moment on, with the strong exception of a few upper-bracket types such as Dylan, Lennon and McCartney, pop music was both compromised and downsized.

JW: So we have them to blame for the shift?

WF: Not them specifically. The big chasm in pop history isn't so much the gap between crooners and rockers but, instead, between “pure" singers and composers and the all-in-one singer-player-songwriters who think they can do it all.

JW: Wasn't the result something of an improvement, a shift away from “moon-June" and toward more meaningful, personal storytelling?

WF: Songwriter Jimmy Webb told me about a comment he heard from Joni Mitchell: “We used to have lyricists, we used to have composers, we used to have singers, we used to have accompanists and arrangers. Now we have one person doing all those jobs and in a half-assed way!"

JW: I notice that Astrud Gilberto, Georgia Gibbs and Dionne Warwick didn't make the cut for your book. Why not?

WF: The focus, first of all, was on artists who sang the American Songbook. But even though I cover 150 to 200 singers, from the age of wax cylinders to the age of MP3s, no book is going to be big enough to cover everybody. The focus was on artists who were iconic, influential and incredibly great.

JW: In a nutshell, what was the criterion?

WF: I wanted to feature singers who had a lasting impact on the way that the Songbook has been sung. Obviously there was a great deal of subjectivity. I had to make the case for a number of artists who were outside of my personal taste. Likewise, my editor Bob Gottlieb would request the inclusion of singers I hadn't thought of.

JW: So did Gilberto and Warwick not qualify or were they overlooked?

WF: Neither Gilberto nor Warwick, as far as I know, sang the Songbook exclusively, or frequently enough to warrant inclusion. Besides, I never thought of either one of them as heavy hitters.

JW: How so?

WF: Gilberto was the first to make a practice of bringing the bossa nova to North American songs, for which she deserves credit. But I always thought of her voice as colorless and flat. Someone once said that she sings with all the pizzazz of a UN interpreter. As for Warwick, I honestly have never paid much attention to her. Your recent interview and post on her may cause me to re-think my position.

JW: What about Georgia Gibbs?

WF: There are a few references to Gibbs in the book, but I had to make a judgment call there. Frankly, her career wasn't big enough. She didn't have hits that compete with Jo Stafford's or Patti Page's. And as a stylist, I don't think she really competes with Peggy Lee or Blossom Dearie.

JW: What do you think of Gibbs?

WF: She was a talent and she had a long career. But she never really attained the upper brackets in her band-singer phase or as a solo act in the 1950s, when she was viewed, incorrectly, merely as a cover artist.

JW: What then were the qualifications?

WF: I was looking for artists who were either incredibly popular—with big massive careers—or incredibly influential. The two aren't necessarily related. Frankie Laine sold a zillion records and was massively popular. But nobody tries to sound like him. As for incredibly great but less popular, two examples are Jeri Southern and Joe Mooney. Both had relatively small careers but were disproportionately influential.

JW: Why do we hear today endless American Songbook renditions but so few interpretations of '60s and '70s songs?

WF: With good reason. When singer and songwriter and arranger and accompanist were separate professions, the songs that came out of that era were essentially intended to serve as templates for interpretation (and even improvisation).

JW: What do you mean?

WF: When Harold Rome wrote the score for Call Me Mister in 1946, he knew that whoever sang his songs on Broadway would do it one way. Whatever big bands recorded it would play it a different way, the pop singers who sang it on the radio would do it their own way, and the more distinctly jazz-oriented stylists of the era, from Ella Fitzgerald to the King Cole Trio, would find yet another way to do the same song.

JW: Songs from the 60s and '70s were crafted differently?

WF: They didn't lend themselves to the same kind of interpretation. From the Beatles and Bob Dylan onward, it was generally expected that the composer and performer would be the same person—occasionally for better, generally for worse.

JW: Aren't we splitting hairs? Music is music and a good song is a good song, no?

WF: Yes, but the point I'm making is that the Songbook lends itself better to interpretation. The songwriter and singer Dory Previn made an interesting distinction. She said that when she was writing songs with her then-husband Andre Previn in the early '60s, she describes that traditional style of songwriting as “objective." Ten years later, when she was writing her own songs—music and lyrics—and singing them herself, she calls that kind of songwriting “subjective."

JW: Meaning?

WF: The songs she wrote later in the singer-songwriter era could pretty much be sung only by her. They were so personal and came so directly out of her unique experience. But this goes beyond just lyrics.

JW: In what regard?

WF: Pianist Bill Charlap once pointed out to me that songs written mostly for Broadway and Hollywood in the years before 1960 were explicitly constructed harmonically and melodically to encourage interpretation. They use higher intervals—ninths and beyond—which open up a wide range of harmonic possibilities. The post-1970 singer-songwriter songs don't have that inherent musicality, and, consequently, there's only so much you can do with them.

JW: So songs by James Taylor are out?

WF: Nothing against James Taylor, but it's much harder to improvise on one of his songs than on something by Cy Coleman.

JW: Does this extend to post-1960s Broadway?

WF: Yes. Since 1970, Broadway's music has been much more “subjective." In the aftermath of Stephen Sondheim, songs tend to be more and more completely integrated into the plots of their shows, and harder to extract and make work independently. Sondheim is far from tuneless and amusical, of course. I think he's an even better composer than he is a lyricist. But there's a reason why the Shelly Manne Trio never recorded a jazz treatment of Sondheim's Pacific Overtures.

JW: Are we treating 1960 a bit like some continental divide?

WF: No, no. I'm not saying that there haven't been dozens or even of hundreds of excellent songs written in the last 50 years. But whatever the total, it's nothing, not even a drop in the bucket, compared to the thousands upon thousands of great songs written, as they say, back in the day.

JW: Can too much pop ambition and polish spoil a jazz interpretation of the Songbook?

WF: I have heard people say that, but I don't know if it's necessarily true. Some voices are smooth and polished and others are rough and scabrous. Some singers have more appealing natural voices than others, but obviously it's what you do with it that counts.

JW: For example?

WF: Joe Mooney could barely whisper in tune, yet he phrased so brilliantly that singers like Tony Bennett and Frank Sinatra cited him as an influence. With her tiny, baby-doll voice, Blossom Dearie had one of the most distinctive sounds around.

JW: Is the opposite true as well?

WF: Yes. I don't think there is such a thing as a “jazz voice" sound, unless it sounds exactly like Louis Armstrong's. We associate the rougher voices with the blues—like the crackling chops of Ray Charles. But Joe Williams had a voice smoother than most crooners. If Ella Fitzgerald had improvised less and concentrated more on looking for hit singles, she could have easily competed in the pop stakes with Jo Stafford and Nat King Cole. Sarah Vaughan probably could have sung Puccini or Verdi with a little effort—certainly better than Aretha Franklin.

JazzWax pages: Will Friedwald's A Biographical Guide to the Great Jazz and Pop Singers (Pantheon) can be found here.

Five more picks. I asked Will Friedwald for a list of his 10 favorite little-known albums by jazz and pop singers. Here's the second set on his list. The first five are in Part 1 of this interview. Five more, in alphabetical order:

6. Jackie Paris: The Song is Paris (Impulse) 7. Louis Prima: On Broadway (United Artists) 8. Frank Sinatra: Close to You (Capitol) 9. Jeri Southern: You Better Go Now (Decca) 10. Kay Starr: I Cry By Night (Capitol)

JazzWax clip: Think you know Kay Starr? Here she is singing Baby Won't You Please Come Home from I Cry By Night with Mannie Klein (tp), Gerald Wiggins (p), Al Hendrickson (g), Joe Comfort (b) and Lee Young (d) (Ben Webster appears on other tracks on the album)...

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.