During the 1950s, Herb (and Lorraine) recorded on some of the best albums of the decade. In addition to the albums Herb recorded as a leader, he was a popular sideman on albums with Clifford Brown, Maynard Ferguson, Buddy Rich, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Shorty Rogers, Russ Garcia, Mel Torme, Anita O'Day and many others.

In Part 4 of my five-part interview with Herb, the West Coast alto saxophonist giant talks about Jimmy Giuffre, Art Pepper, Maynard Ferguson, Clifford Brown, Max Roach, Frank Butler and Larance Marable:

JazzWax: You and your wife Lorraine were early All Stars at The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach.

Herb Geller: Yes, Lorraine became the house pianist there after Claude Williamson left. There were three bands a day, each one playing for four hours. I played with Shorty Rogers, Jimmy Giuffre, Bud Shank, Bob Cooper, Conte Candoli and others. Max Roach replaced Shelly after he left. Max was happy to come to L.A. in 1953. He said he was getting tired of New York and wasn't getting as many gigs there as he would have liked.

JW: How was Jimmy Giuffre?

HG: I never got along with him that well. I think he must have thought I was a Charlie Parker imitator, which, of course, I wasn't. I was trying to establish my own sound. Bud Shank, who I played with in many bands, was always copying Art Pepper.

JW: Was Art Pepper well liked?

HG: Not really. He was an impossible person. He was mixed up with drugs and had a big complex about Charlie Parker. What Art was really trying to do was play the alto like Zoot Sims played tenor. Art never had that much talent but put enormous personality into that horn. To his credit, there was a certain sound quality and swinging feeling there, and when he was on, his sound was special.JW: Was there a West Coast sound?

JW: What did Shad have you do?

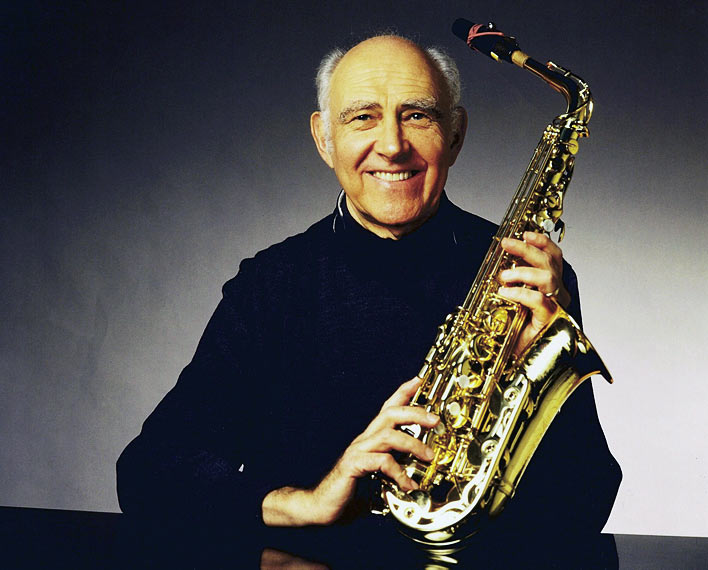

HG: Yes--but there were really two West Coast sounds. Live dates were different than recording sessions. For gigs, everyone played bebop because it was more exciting for audiences. In recording sessions, leaders tended to write arrangements that were more harmonic and voiced. [Pictured: A live session at The Lighthouse]

JW: Your sound on the alto sax was always singular and identifiable.

HG: I was never interested in what everyone else was doing. I was always trying to find a new way and to learn new tunes. Lorraine and I became involved with learning as many songs as possible by different composers--Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Jimmy Van Heusen, Jule Styne and so on. We did this to build a big repertoire. I don't think anyone knew as many songs as Lorraine and I did back then.

JW: You played often with trumpeter Don Fagerquist.

HG: He was wonderful. Don was my soulmate on trumpet. We had similar sounds--even though we played different instruments. We both knew where we wanted our solos to wind up and both looked for that pure tone.

JW: How would you describe the difference between Chet Baker and Fagerquist?

HG: Chet was about instinct and talent. Don had knowledge. His main gig had been playing with the Les Brown band, which was a very polished outfit. But he couldn't stand it any more by the mid-50s and quit.

JW: You also played and recorded frequently with Maynard Ferguson.

HG: All of my EmArcy dates, starting in 1954, came through Maynard. I was working with him at the time when he called to tell me that he was getting a Mercury contract. He said he was asked to recommend other musicians and that he recommended me. The producer was Bob Shad, who was head of a&r at Mercury and had founded EmArcy.

HG: Three albums under my name. It was great because I could use Lorraine, which meant double pay since we were married [laughs]. We made some pretty good money.JW: Plus all those jam session albums for EmArcy.

HG: That's right. Bob Shad put together everyone who was under contract to the label--Dinah Washington, Maynard Ferguson, Clifford Brown, and everyone else. It was sort of like Jazz at the Philharmonic, but just EmArcy artists. Clifford Brown was the greatest. Personally, he was an angel. You couldn't ask for a finer person. He never smoked, drank or swore. He was true to his wife. And he was such a gentleman. Everyone looked up to him. We talked all the time on the phone about chords and phrasing. His passing was such a shame.JW: When did you first meet Brown?

HG: Years earlier. When Max was at The Lighthouse in 1953, he had always talked about putting together his own band. Eventually Max left The Lighthouse and sent for Clifford Brown and Richie Powell who were back East. Teddy Edwards joined but soon left. He was replaced by Harold Land. I knew Clifford from Atlantic City. When I was with Billy May in 1952, we did a week at the Steel Pier. There was a club nearby that had jam sessions that started at 10 p.m. and ended at 3 a.m. Everyone would come in and jam after hours. One of the first people I met there was Clifford Brown. He was playing in a rock and roll band. Oliver Nelson was there, too.JW: In 1955 you and Lorraine moved to a larger house.

JW: What did he say to you?

HG: The work was picking up and we wanted a place without neighbors so our playing and practicing wouldn't disturb anyone. We put an ad in the papers for a secluded home. A guy called and said he had the perfect house for us in the Hollywood Hills. It had a big built-in kitchen, appliances, two bedrooms, a dining area and a fireplace. We had saved up enough for a third of the payment and took out a mortgage for the rest. Lorraine brought her big grand piano down from Portland, OR, and we put my mother's piano in the other bedroom.

JW: Did you have parties?

HG: We had a house warming party you wouldn't have believed. Every jazz musician in L.A. was there--Shelly Manne, Shorty Rogers, you name it. We were jamming in one room, Milt Jackson was in another room, Scott LaFaro in another. When Scott came to town we let him stay in our second bedroom.

JW: Was there competition between Shelly Manne and Max Roach while Max was in L.A.?

HG: No. But other musicians compared them all the time. Larance Marable, my drummer, said he wasn't crazy about Max. He said Max rushed the beat. Larance said he wasn't really with the soloist and didn't get inside the tempo. At the time, I didn't understand that special nuance. I asked him who in his opinion did do those things. He said Art Blakey and Kenny Clarke.

JW: Did you play with them?

HG: Yes. I recorded with Max on several albums, jammed with Art and worked with Kenny, recording with him in the early 1970s. I would always rather play with Kenny than Max. No matter how fast the tempo, Max would always play faster. For me, my lines couldn't come out as well as I had hoped with Max doing that.

JW: Was Maynard Ferguson's Dream Band of 1956 truly a dream band?

HG: Was it ever. Maynard was so great. What an instrumentalist. He had a great sense of humor and was very relaxed and confident. One day Maynard called me and said he had a chance to go to New York to work for three weeks at Birdland and record two albums. He said it would feature only Local 802 guys and asked if I wanted to go. Fortunately I had my card and was paid up, so I went.

JW: Did you arrange for the band?

HG: Yes, Nightmare Alley. It was the first big band chart I ever wrote. It was a mid-tempo ballad. I also wrote Geller's Cellar, which featured me in an extended solo. When I left the band and saxophonist Jimmy Ford came in, Maynard re-named it Watch the Ford Go By and when Lanny Morgan joined, he called it Morgan's Organ. All the charts for that Dream Band were sensational. They were written by Johnny Mandel, Al Cohn, Manny Albam, Ernie Wilkins, Bill Holman, Bob Brookmeyer and others. Maynard was like a circus performer. Everyone was knocked out.

JW: That was some reed section.

HG: It was a thrill. I was sitting next to Al Cohn and Budd Johnson, and Ernie Wilkins was on baritone sax. Not to mention the trumpets, trombones and rhythm section.

JW: L.A. in the 1950s sounds like it offered musicians enormous work opportunities.

HG: It did. I'll give you an example of what could happen. Toward the end of 1955, I was playing a striptease joint on Sunset Boulevard. All the movie stars came in. One of these guys was Gary Crosby, Bing's son. He would come in and always send drinks up to the band. He even knew our names. He was very very friendly.

HG: One night Gary said, “Herb, I have to go into the Army. I'm having a farewell party in Malibu. Would you come and bring your sax and sit in?"

JW: What did you say?

HG: I said, “Sure. Can my wife come and play piano?" He said, “Sure." So we went out to his house in Malibu. A guy was playing piano but only knew two tunes. There was no bass. So Lorraine and I got in there and did our thing. The next day I got a call from the No. 1 contractor for film studios. He had been at the party.

JW: Contractors were key.

HG: They controlled all of the work, and the most lucrative jobs were recording on movie soundtracks. The contractor on the phone says, “Arranger Buddy Bregman is crazy about your playing. He wants you on his record date next week. I said great, I'll be there.

JW: What happened?

HG: I get to the date and the guy who called me is there. I hadn't played a single note yet. He said to me, “Do you have your calendar? Open it up." I did and he gave me about four record dates, and I hadn't even played yet. There was that much work.

JW: In 1956, you record Mel Torme Sings Fred Astaire with Marty Paich's Dek-Tette.

HG: I didn't play flute at the time, so Bud Shank and Ronnie Lang got a lot of that Dek-Tette work that Marty put together. But for the Mel Torme album, Marty just needed an alto so he called me. Mel was a brilliant, fantastic musician. He was naturally talented and had pure jazz swing. You can hear all of it on that album.

JW: What about your Fire in the West album in 1957?

HG: I wrote the arrangements and called for a rehearsal because I wasn't sure of Kenny Dorham's reading ability. We were scheduled to meet at my house at 2 p.m. The night before I called my drummer Frank Butler and said “Do you have drums?" He said, “Yes." I said, “A car?" He said, “Yes. I'll be there."

JW: What happened?

HG: Well, at 2 p.m. there's no Frank Butler. I was angry. Everyone was angry. I called Larance Marable. Fortunately Larance was home and said he could be at my house in a half hour. He arrived and we rehearsed.

JW: What did Frank say?

HG: The next day Frank called and asked, “When is the recording?" I told him, “Next week. But Larance Marable is going to do it. You promised to be at the rehearsal and you weren't there." Frank [pictured] said, “I got hung up. I'm sorry." I said “Larance is the drummer on the session, that's final." Frank said, “I'm not forgetting that."

JW: What happened?

HG: Two months later, I came home to my house to find a window had been forced open and my TV, sports shirts and some cash was gone. The house had been ransacked.

JW: Who do you think did it?

HG: Two weeks later, Miles Davis came into town with Philly Joe Jones, a dear friend. Philly came up to my house and said, “Hey, didn't you used to have a white Philco TV set?" I said, “Yes." Philly Joe said, “Frank Butler has it." A short time later Frank was arrested for breaking into another home. Frank was a brilliant drummer but he just couldn't get it together. He was a sick man. He was in jail a lot of years.

JW: Do you dig your 1950s recordings?

HG: I really don't enjoy listening to them. They make me nervous. You hear the music. I hear things I would have done differently.

Tomorrow, Herb talks for the first time about the sudden death of his wife Lorraine in 1958--what happened, the impact of her loss on his spirit, his subsequent move to Germany in 1962 and the start of a new life and family.

JazzWax tracks: There are simply too many exciting albums by Herb to mention here. I will simply list the ones I love best from the 1950s, but be aware there are many, many more:

- Maynard Ferguson Octet (1955); available as a download.

- Around the Horn with Maynard Ferguson (1955); download.

- Shorty Rogers--Clickin' With Clax (1956); import.

- Listen to the Music of Russ Garcia (1956); on Los Angeles River CD from Fresh Sound.

- Maynard Ferguson--The Birdland Dream Band (1956); on Fresh Sound CD.

- Mel Torme Sings Fred Astaire (1956); download.

- Herb Geller--Fire in the West (1957); on That Geller Feller from Fresh Sound.

- Shorty Rogers--Portrait of Shorty (1957); on CD.

- Manny Albam--Jazz Greats of Our Time (1957); import CD.

- Don Fagerquist--Eight by Eight (1957); download and CD.

- Annie Ross--Gypsy (1959); on CD, used.

- Art Pepper--Plus Eleven (1959); download and CD.

JazzWax clip: Here's Herb in Germany in 2009 recording Indiana with the Darmstdter big band. Listen as the arrangement leaps into Miles Davis' Donna Lee toward the end...

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved.