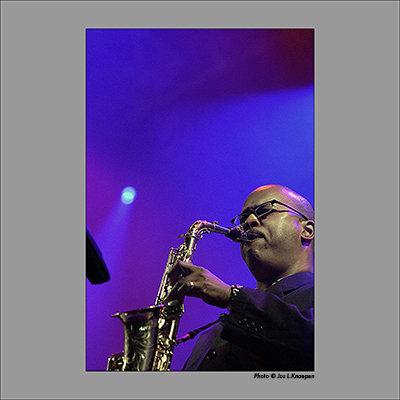

Continuing our dialogue on the audience equation for creative music, which heretofore has focused on the puzzling conundrum of the African American audience, the always thoughtful saxophonist-composer and record label (Inner Circle www.innercirclemusic.com) head Greg Osby weighs in on the audience in general, with a particular emphasis on calling into question musicians who only seem to play for their own self-aggrandizement and that of their peer musicians.

A recent conversation with one of my colleagues was both illuminating and also sad at the same time. My friend, who had just completed a lengthy tour, was lamenting that for the entire duration of the tour, he felt that the audiences just didn't “get him" or were oblivious or apathetic to his mission as an artist. ("They just weren't hearing me, Man.") I attempted to reassure him that we, in improvised music, are often subjected to blank stares and less than ideal responses to much of our proud work that we may have spent a great deal of time developing. Our audience numbers and the amounts of positive feedback are considerably lower than that for other situations that usually have fewer demands on them in terms of sacrifice, intent or pure artistry. This is a fact that we have been conditioned to regard as normal and therefore have accepted.

I have often struggled with this notion myself, given that I have endeavored to be as provocative and progressive with my work as is necessary in order to inspire myself and my bands, as well as to leave the audience with imagery that would be reflective of my full artistic intentions and purpose. Producing experimental, risk-taking music and stretching conceptual parameters has been what my peers and I consider to be quite normal, and we impose very specific expectations on ourselves as well as on each other concerning how things should progress or be constructed. However, what I consider normal and acceptable has often been dismissed as “cerebral, left-of-center, “cutting edge," and I am often called a maverick or even controversial. Although I understand the need for description, it has dawned on me that these labels, as well as my failure to connect with audiences outside my own artistic indulgences are what, on a broader scale have served to fail the music in terms of “reaching the people on a very basic level.

My current dilemma was more clearly illustrated when I played a few tracks from my latest release “9 Levels" a year ago for my sister in St. Louis. Mind you, my sister has never been one to tactfully withhold her opinion. Although never deliberately malicious, her candor has a sting to it that is often misinterpreted. After listening to said tracks, I wanted her honest overview of what she'd heard. Her response, although jarring, was quite possibly the eye/ear opener that I'd needed, and it was probably necessary that I'd heard it from a loved one as opposed to someone with a questionable agenda. She said that my work sounded like Mad Clown Music, and that it gave her the impression similar to that of a multi-act circus with the sword swallower in one ring, multiples of clowns trying to fit in a small car in the next, acrobats on the flying trapeze and trained seal, lions and elephants—all going on at once. To her, it was impossible for her to focus on any one element because so much information was bombarding her auditory senses at the same time.

At that point, I understood the reasons for the blank looks at concerts, the off-base reviews, the empty seats, the refusal of agents and promoters to book my groups, etc. What has been normal for me is anything but normal for laypersons and even some learned aficionados. It was brought to my attention that in order to make a connection with “the folk," it is not necessary for musicians to pelt them with layers of stylized content and high concept all the time. Such displays of artistic self-indulgence are best left for schools or audiences that are comprised of primarily students or fellow musicians. We simply have to understand and accept that everyone cannot adequately decipher long-winded barrages of notes and musical content. It would be like going to a restaurant and eating a dish of one's favorite food that had been over-seasoned with too many ingredients—after a point, it would be impossible to taste the actual food anymore as it's flavor and intent would have been obscured by the zealous and heavy-handed overkill of too many spices.

One must consider that this is not an easy task for any contemporary improvising musician to carry out, where one's prowess is judged based on an extreme knowledge and execution of advanced content, knowledge and achievement—all displayed with as much virtuosic flair as possible each time you play. In many music circles, anything less is considered unacceptable. But the fact remains that the only people who actually have consistent positive responses to such pyrotechnics all happen to be other musicians—none who contribute to keeping the bills paid at a venue. Most get in clubs for free and almost never buy CDs anyway. So why then should it be so important for players to play so much, all the time just so your friends can high five each other and remark of how “baad" you are?

Musicians will have to understand, in the scheme of salvaging the remaining support base for the music, that it is no longer acceptable to present music in such a fashion and that the paying public should be their primary concern—not producing music that is designed exclusively for other musicians. We will have to ask ourselves if patrons are responding favorably to well crafted and completely developed works and if they are truly being inspired by the musical stories that are being told? Are they being delivered life-changing impressions through musical organization? Or are they being bombarded with endless run-on sentences of superfluous content, as if in a firing squad where the notes are functioning as sonic bullets? Musicians would do well to produce music with both experienced and uninitiated listeners in mind, and must proceed with the knowledge that not everyone hears as we do. This is not to say that there is no longer room for intellectual excursions and reckless flights of fancy, but artists will have to me mindful of just who their targeted demographic and listener base is, or needs to be. I, for one, have no desire to be subjected to several 15 or 20 minute compositions in a row, lengthy solos, unnecessarily complicated pieces that have no discernable primary melody (yes, I'm guilty) and sullen, meandering pieces that don't make their point. If I, a veteran musician, can no longer tolerate it, (and neither can my sister...) then I certainly can't blame paying audiences or booking entities for not responding favorably or supporting such overwhelmingly self-indulgent output as well.

Ahmad Jamal, Bill Evans, Ben Webster, Miles Davis, Count Basie, Paul Desmond, Shirley Horn, etc...each made some incredibly profound statements without over saturation. Lesson learned.

A recent conversation with one of my colleagues was both illuminating and also sad at the same time. My friend, who had just completed a lengthy tour, was lamenting that for the entire duration of the tour, he felt that the audiences just didn't “get him" or were oblivious or apathetic to his mission as an artist. ("They just weren't hearing me, Man.") I attempted to reassure him that we, in improvised music, are often subjected to blank stares and less than ideal responses to much of our proud work that we may have spent a great deal of time developing. Our audience numbers and the amounts of positive feedback are considerably lower than that for other situations that usually have fewer demands on them in terms of sacrifice, intent or pure artistry. This is a fact that we have been conditioned to regard as normal and therefore have accepted.

I have often struggled with this notion myself, given that I have endeavored to be as provocative and progressive with my work as is necessary in order to inspire myself and my bands, as well as to leave the audience with imagery that would be reflective of my full artistic intentions and purpose. Producing experimental, risk-taking music and stretching conceptual parameters has been what my peers and I consider to be quite normal, and we impose very specific expectations on ourselves as well as on each other concerning how things should progress or be constructed. However, what I consider normal and acceptable has often been dismissed as “cerebral, left-of-center, “cutting edge," and I am often called a maverick or even controversial. Although I understand the need for description, it has dawned on me that these labels, as well as my failure to connect with audiences outside my own artistic indulgences are what, on a broader scale have served to fail the music in terms of “reaching the people on a very basic level.

My current dilemma was more clearly illustrated when I played a few tracks from my latest release “9 Levels" a year ago for my sister in St. Louis. Mind you, my sister has never been one to tactfully withhold her opinion. Although never deliberately malicious, her candor has a sting to it that is often misinterpreted. After listening to said tracks, I wanted her honest overview of what she'd heard. Her response, although jarring, was quite possibly the eye/ear opener that I'd needed, and it was probably necessary that I'd heard it from a loved one as opposed to someone with a questionable agenda. She said that my work sounded like Mad Clown Music, and that it gave her the impression similar to that of a multi-act circus with the sword swallower in one ring, multiples of clowns trying to fit in a small car in the next, acrobats on the flying trapeze and trained seal, lions and elephants—all going on at once. To her, it was impossible for her to focus on any one element because so much information was bombarding her auditory senses at the same time.

At that point, I understood the reasons for the blank looks at concerts, the off-base reviews, the empty seats, the refusal of agents and promoters to book my groups, etc. What has been normal for me is anything but normal for laypersons and even some learned aficionados. It was brought to my attention that in order to make a connection with “the folk," it is not necessary for musicians to pelt them with layers of stylized content and high concept all the time. Such displays of artistic self-indulgence are best left for schools or audiences that are comprised of primarily students or fellow musicians. We simply have to understand and accept that everyone cannot adequately decipher long-winded barrages of notes and musical content. It would be like going to a restaurant and eating a dish of one's favorite food that had been over-seasoned with too many ingredients—after a point, it would be impossible to taste the actual food anymore as it's flavor and intent would have been obscured by the zealous and heavy-handed overkill of too many spices.

One must consider that this is not an easy task for any contemporary improvising musician to carry out, where one's prowess is judged based on an extreme knowledge and execution of advanced content, knowledge and achievement—all displayed with as much virtuosic flair as possible each time you play. In many music circles, anything less is considered unacceptable. But the fact remains that the only people who actually have consistent positive responses to such pyrotechnics all happen to be other musicians—none who contribute to keeping the bills paid at a venue. Most get in clubs for free and almost never buy CDs anyway. So why then should it be so important for players to play so much, all the time just so your friends can high five each other and remark of how “baad" you are?

Musicians will have to understand, in the scheme of salvaging the remaining support base for the music, that it is no longer acceptable to present music in such a fashion and that the paying public should be their primary concern—not producing music that is designed exclusively for other musicians. We will have to ask ourselves if patrons are responding favorably to well crafted and completely developed works and if they are truly being inspired by the musical stories that are being told? Are they being delivered life-changing impressions through musical organization? Or are they being bombarded with endless run-on sentences of superfluous content, as if in a firing squad where the notes are functioning as sonic bullets? Musicians would do well to produce music with both experienced and uninitiated listeners in mind, and must proceed with the knowledge that not everyone hears as we do. This is not to say that there is no longer room for intellectual excursions and reckless flights of fancy, but artists will have to me mindful of just who their targeted demographic and listener base is, or needs to be. I, for one, have no desire to be subjected to several 15 or 20 minute compositions in a row, lengthy solos, unnecessarily complicated pieces that have no discernable primary melody (yes, I'm guilty) and sullen, meandering pieces that don't make their point. If I, a veteran musician, can no longer tolerate it, (and neither can my sister...) then I certainly can't blame paying audiences or booking entities for not responding favorably or supporting such overwhelmingly self-indulgent output as well.

Ahmad Jamal, Bill Evans, Ben Webster, Miles Davis, Count Basie, Paul Desmond, Shirley Horn, etc...each made some incredibly profound statements without over saturation. Lesson learned.