No one knows more about soul jazz and the jazz organ combo than Bob Porter. That's because he produced many of the great recordings of the late 1960s and '70s for Prestige and often wrote the liner notes. He also produced other organ combo sessions in the '80s and beyond. Bob has spent more than 30 years on WBGO-FM in Newark, N.J., hosting Portraits in Blue on Fridays at 6:30 p.m. and Saturdays at 7 a.m. (EST); Saturday Morning Function, from 8 to 10 a.m. (EST); and Swing Party on Sundays from 8 to 10 a.m. (EST).

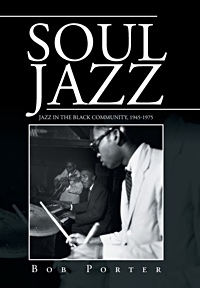

Bob also is the author of the new book, Soul Jazz: Jazz in the Black Community, 1945-1975 (Xlibris) (go here). Last time I interviewed Bob, we talked about soul-jazz and five of his favorite albums (go here). Today, we talk about the jazz organ combo:

JazzWax: Why were so many of the best organ combo albums recorded for Prestige?

Bob Porter: The organ combo sound on Prestige started with tenor saxophonist Eddie “Lockjaw" Davis and organist Shirley Scott in 1958. Producer Esmond Edwards brought them to the label, but owner Bob Weinstock decided to produce the first sessions by each himself. He was interested in having Shirley as a regular artist on Prestige and wanted their first Cookbook installment to be a one-shot.

But Esmond convinced him to sign “Lockjaw" Davis to an exclusive contract. When Esmond became Prestige's recording director a couple of months later, the label's approach changed. Esmond was raised in Harlem and at the time Harlem was loaded with little organ clubs. It is the music that came out of Harlem's neighborhoods and it's the sound Esmond wanted to Prestige.

Bob was game. He always loved the blues. I think he viewed the organ groups as a natural instrumental extension. During the period that Esmond produced for the label, between 1958 and 1962, organ combos began to flower in clubs and at Prestige. I cover this period extensively in my book Soul Jazz.

My tenure at Prestige started in 1968, following producers Ozzie Cadena and Cal Lampley. Although Ozzie had a huge record with Jack McDuff's Screamin' (1962), he wasn't really an organ guy. Neither was Cal, but he had big records with Johnny “Hammond" Smith and Richard “Groove" Holmes. Then the soul jazz perspective at the label dimmed. When Don Schlitten at Prestige hired me in '68, my task was to rebuild that part of the label, since Don had a whole roster of his own artists he wanted to record.

JW: What were the secret ingredients for getting the best possible performance from organists?

BP: I don't know if there was any secret ingredient. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder and I talked about making records on several occasions. We both agreed that in terms of music and audio, we wanted to make records that sounded good on the radio. The musicians always had the final say on which take to use, but often we would go with the take with the best feeling rather than the one with the most precise execution.

JW: Which organists had the most interesting drawbar settings that produced quirky sounds?

BP: The organists were very secretive about the specific settings they used. In almost each case, an organist would eliminate their particular setup once the session was over. Drawbars were all pushed in and wiped clean. Each organist had his or her own special range of tricks to get a unique sound. For example, “Groove" Holmes would turn the organ off and then back on to get a weird sound. Johnny “Hammond" Smith would get different effects from the Leslie speakers that he used. Charlie Earland loved to use drone settings.

JW: Which organists who you recorded are virtually unknown today and what made them special?

BP: To the general public, nearly all the organists from back then are unknown today. The heyday of that music dates back well into the 20th century. Of those remaining, Dr. Lonnie Smith and Rhoda Scott still do it to my taste. Of the younger players, I love Akiko Tsuruga. She has great personality. But to your question, a story: Guitarist Melvin Sparks brought in organist Leon Spencer Jr. to play on his first leadership album, Sparks! (1970). I subsequently signed Spencer—not because he was a great player but because he wrote good tunes. Often when players would come in from out of town, they did not bring a band. So we had to construct a setting for them. To have Spencer on a date meant that we would have quality original material. Tenor saxophonist Rusty Bryant occasionally would bring in an organist from Ohio for his dates. On one occasion, he brought Wilbert Longmire as well as Bill Mason. I had Spencer booked for the session, but Rusty wanted to hear Mason on a couple of tunes. Spencer contributed and played on a funky blues entitled The Hooker. But then Mason took over on a Bryant song that became the album's title track, Fire Eater (1971), and blew the roof off the place. I recorded Mason for Gettin' Off (1972) but lost touch with him afterward. Guys kept bringing in new guys.

Organist Sonny Phillips, from an earlier time, also was a fine accompanist and wrote great tunes—including tenor saxophonist Houston Person's big hit Jamilah. Sonny wrote the arrangements for Pucho & the Latin Soul Brothers's Jungle Fire (1970), and I forgot his arranging credit on the album! Today, Sonny lives in California. His leadership albums were group events based on his original tunes.

JW: Whose idea was it to use contemporary soul songs as the basis for tracks?

BP: Jazz players have always used popular tunes of the day in their own way. I think Harold Mabern made me aware of Motown tunes when he brought in I Heard It Through the Grapevine [from Rakin' and Scrapin' in 1968] and Too Busy Thinking 'Bout My Baby [from Workin' and Wailin' in 1969]. Pretty soon most of the guys were doing it. At one point, I was using so many Motown tunes published by Jobette Music that Carl Griffin, who was running Jobette at the time, called up to thank me. As far as the horn sound, the key guy here was Virgil Jones. He was a favorite of Johnny “Hammond" Smith and Houston Person—who probably recommended him. Mabern used him on a date, so we started using him with almost everyone, including Houston, Melvin Sparks, Sonny Stitt, Charles Kynard and Charlie Earland. I remember Melvin once remarking that Virgil was the best trumpet player that nobody knew. If I had stayed longer at Prestige, I'm sure I would have done something with him as a leader.

JW: What are your five favorite organ combo albums that you produced?

BP: Here are my five favorites, in no particular order:

Jimmy McGriff—Movin' Upside the Blues (1981/JAM). Of all the organists I've worked with, McGriff was the best blues player. “Blues player" is a term you don't hear much these days, but back in the day it was a term of great respect. Jimmy would describe himself as a blues organist. There are two tunes that really ring true for me—an unlikely treatment of Moonlight Serenade and a Les McCann tune called Could Be. The alto saxophonist, Arnold Sterling, and the drummer, Vance James, were both from Baltimore and were perfect for Jimmy. The guitarist was Jimmy Ponder, who was always aces in an organ combo context.

Rusty Bryant—Soul Liberation (Prestige, 1970). This album was a big hit. It must have sold at least 75,000 units. This is the same band on Charles Earland's Black Talk, but with Rusty instead of Houston Person. It was a consistent album with solid playing on every song. The title track contains a moment when Rusty's solo and the rhythm section hit a perfect groove. Organist Charlie Earland and drummer Idris Muhammad are wonderful on this album. Virgil has a great solo on Cold Duck Time, a version I like better than Eddie Harris's.

Willis Jackson—Gator's Groove (Prestige, 1968). Gator could be a pain-in-the-ass but he and Bill Jennings worked so well together that I have forgotten everything but the good stuff. Willis Jackson could really make a slow-medium groove such as This Is the Way I Feel work better than anyone. Willis liked to use his working band (Jennings, organist Jackie Ivory and drummer Jerry Potter), so we just added conga drum. It's a little surprising to hear Long Tall Dexter in this context, but it sure works. Sadly, this never made the jump to CD.

Charles Kynard—Afro-Disiac (Prestige, 1970). I produced five albums with Kansas City Charlie [Kynard], and this is my favorite. Any time we could get Grant Green was a special occasion. He and Houston Person were a mutual admiration society and the team of Jimmy Lewis and Purdie works so well together. There is a tune on this album titled Odds On where Kynard runs both manuals at the same time and creates a vision of Oscar Peterson on organ. This one was breaking in Detroit but then the auto workers went on strike. Game over. Sometimes you must be lucky.

Plas Johnson and Red Holloway—Keep That Groove Going! (Milestone, 2001). I had two objectives here: one was to get Red into a competitive setting, which he hadn't done since his days with Sonny Stitt in the 1970s. The second was to get Plas recorded at Rudy Van Gelder's. We did a second album with Red and Frank Wess called Coast to Coast that includes Good to Go, the theme song of my Swing Party show on WBGO. I wanted to get Clifford Solomon into this situation, but it was too late. By then, he was too sick to play. Pass The Gravy is my favorite performance. The organist is Gene Ludwig, from Pittsburgh, another fine player. And like so many, rarely recognized for his talents.

Bob also is the author of the new book, Soul Jazz: Jazz in the Black Community, 1945-1975 (Xlibris) (go here). Last time I interviewed Bob, we talked about soul-jazz and five of his favorite albums (go here). Today, we talk about the jazz organ combo:

JazzWax: Why were so many of the best organ combo albums recorded for Prestige?

Bob Porter: The organ combo sound on Prestige started with tenor saxophonist Eddie “Lockjaw" Davis and organist Shirley Scott in 1958. Producer Esmond Edwards brought them to the label, but owner Bob Weinstock decided to produce the first sessions by each himself. He was interested in having Shirley as a regular artist on Prestige and wanted their first Cookbook installment to be a one-shot.

But Esmond convinced him to sign “Lockjaw" Davis to an exclusive contract. When Esmond became Prestige's recording director a couple of months later, the label's approach changed. Esmond was raised in Harlem and at the time Harlem was loaded with little organ clubs. It is the music that came out of Harlem's neighborhoods and it's the sound Esmond wanted to Prestige.

Bob was game. He always loved the blues. I think he viewed the organ groups as a natural instrumental extension. During the period that Esmond produced for the label, between 1958 and 1962, organ combos began to flower in clubs and at Prestige. I cover this period extensively in my book Soul Jazz.

My tenure at Prestige started in 1968, following producers Ozzie Cadena and Cal Lampley. Although Ozzie had a huge record with Jack McDuff's Screamin' (1962), he wasn't really an organ guy. Neither was Cal, but he had big records with Johnny “Hammond" Smith and Richard “Groove" Holmes. Then the soul jazz perspective at the label dimmed. When Don Schlitten at Prestige hired me in '68, my task was to rebuild that part of the label, since Don had a whole roster of his own artists he wanted to record.

JW: What were the secret ingredients for getting the best possible performance from organists?

BP: I don't know if there was any secret ingredient. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder and I talked about making records on several occasions. We both agreed that in terms of music and audio, we wanted to make records that sounded good on the radio. The musicians always had the final say on which take to use, but often we would go with the take with the best feeling rather than the one with the most precise execution.

JW: Which organists had the most interesting drawbar settings that produced quirky sounds?

BP: The organists were very secretive about the specific settings they used. In almost each case, an organist would eliminate their particular setup once the session was over. Drawbars were all pushed in and wiped clean. Each organist had his or her own special range of tricks to get a unique sound. For example, “Groove" Holmes would turn the organ off and then back on to get a weird sound. Johnny “Hammond" Smith would get different effects from the Leslie speakers that he used. Charlie Earland loved to use drone settings.

JW: Which organists who you recorded are virtually unknown today and what made them special?

BP: To the general public, nearly all the organists from back then are unknown today. The heyday of that music dates back well into the 20th century. Of those remaining, Dr. Lonnie Smith and Rhoda Scott still do it to my taste. Of the younger players, I love Akiko Tsuruga. She has great personality. But to your question, a story: Guitarist Melvin Sparks brought in organist Leon Spencer Jr. to play on his first leadership album, Sparks! (1970). I subsequently signed Spencer—not because he was a great player but because he wrote good tunes. Often when players would come in from out of town, they did not bring a band. So we had to construct a setting for them. To have Spencer on a date meant that we would have quality original material. Tenor saxophonist Rusty Bryant occasionally would bring in an organist from Ohio for his dates. On one occasion, he brought Wilbert Longmire as well as Bill Mason. I had Spencer booked for the session, but Rusty wanted to hear Mason on a couple of tunes. Spencer contributed and played on a funky blues entitled The Hooker. But then Mason took over on a Bryant song that became the album's title track, Fire Eater (1971), and blew the roof off the place. I recorded Mason for Gettin' Off (1972) but lost touch with him afterward. Guys kept bringing in new guys.

Organist Sonny Phillips, from an earlier time, also was a fine accompanist and wrote great tunes—including tenor saxophonist Houston Person's big hit Jamilah. Sonny wrote the arrangements for Pucho & the Latin Soul Brothers's Jungle Fire (1970), and I forgot his arranging credit on the album! Today, Sonny lives in California. His leadership albums were group events based on his original tunes.

JW: Whose idea was it to use contemporary soul songs as the basis for tracks?

BP: Jazz players have always used popular tunes of the day in their own way. I think Harold Mabern made me aware of Motown tunes when he brought in I Heard It Through the Grapevine [from Rakin' and Scrapin' in 1968] and Too Busy Thinking 'Bout My Baby [from Workin' and Wailin' in 1969]. Pretty soon most of the guys were doing it. At one point, I was using so many Motown tunes published by Jobette Music that Carl Griffin, who was running Jobette at the time, called up to thank me. As far as the horn sound, the key guy here was Virgil Jones. He was a favorite of Johnny “Hammond" Smith and Houston Person—who probably recommended him. Mabern used him on a date, so we started using him with almost everyone, including Houston, Melvin Sparks, Sonny Stitt, Charles Kynard and Charlie Earland. I remember Melvin once remarking that Virgil was the best trumpet player that nobody knew. If I had stayed longer at Prestige, I'm sure I would have done something with him as a leader.

JW: What are your five favorite organ combo albums that you produced?

BP: Here are my five favorites, in no particular order:

Jimmy McGriff—Movin' Upside the Blues (1981/JAM). Of all the organists I've worked with, McGriff was the best blues player. “Blues player" is a term you don't hear much these days, but back in the day it was a term of great respect. Jimmy would describe himself as a blues organist. There are two tunes that really ring true for me—an unlikely treatment of Moonlight Serenade and a Les McCann tune called Could Be. The alto saxophonist, Arnold Sterling, and the drummer, Vance James, were both from Baltimore and were perfect for Jimmy. The guitarist was Jimmy Ponder, who was always aces in an organ combo context.

Rusty Bryant—Soul Liberation (Prestige, 1970). This album was a big hit. It must have sold at least 75,000 units. This is the same band on Charles Earland's Black Talk, but with Rusty instead of Houston Person. It was a consistent album with solid playing on every song. The title track contains a moment when Rusty's solo and the rhythm section hit a perfect groove. Organist Charlie Earland and drummer Idris Muhammad are wonderful on this album. Virgil has a great solo on Cold Duck Time, a version I like better than Eddie Harris's.

Willis Jackson—Gator's Groove (Prestige, 1968). Gator could be a pain-in-the-ass but he and Bill Jennings worked so well together that I have forgotten everything but the good stuff. Willis Jackson could really make a slow-medium groove such as This Is the Way I Feel work better than anyone. Willis liked to use his working band (Jennings, organist Jackie Ivory and drummer Jerry Potter), so we just added conga drum. It's a little surprising to hear Long Tall Dexter in this context, but it sure works. Sadly, this never made the jump to CD.

Charles Kynard—Afro-Disiac (Prestige, 1970). I produced five albums with Kansas City Charlie [Kynard], and this is my favorite. Any time we could get Grant Green was a special occasion. He and Houston Person were a mutual admiration society and the team of Jimmy Lewis and Purdie works so well together. There is a tune on this album titled Odds On where Kynard runs both manuals at the same time and creates a vision of Oscar Peterson on organ. This one was breaking in Detroit but then the auto workers went on strike. Game over. Sometimes you must be lucky.

Plas Johnson and Red Holloway—Keep That Groove Going! (Milestone, 2001). I had two objectives here: one was to get Red into a competitive setting, which he hadn't done since his days with Sonny Stitt in the 1970s. The second was to get Plas recorded at Rudy Van Gelder's. We did a second album with Red and Frank Wess called Coast to Coast that includes Good to Go, the theme song of my Swing Party show on WBGO. I wanted to get Clifford Solomon into this situation, but it was too late. By then, he was too sick to play. Pass The Gravy is my favorite performance. The organist is Gene Ludwig, from Pittsburgh, another fine player. And like so many, rarely recognized for his talents.

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved.